Intro to meditation: Class 2 notes

Self compassion, continued

Last time, our discussion of self compassion was cut short. See the class 1 notes for the parts we didn't get to live.

Today, I'll add: self compassion works at several different scales. Moment to moment, while meditating, there is no need to judge yourself when your attention strays from its object. During the course of a sit, it's ok if your experience doesn't match your intended outcome for the sit. And, over time, forgive yourself for not sitting as often as you had hoped to.

When you loosen the grip of self judgment on yourself, you make space for finding solutions to your problems. You will start to associate positive feelings with meditation, and this will condition you to practice more.

Attention and awareness

In order to study concentration practice more deeply, we need some vocabulary and a model of the mind.

Following The Mind Illuminated, we draw a distinction between attention and awareness. Your attention is your mind's ability to select and focus on certain information while ignoring other information. It isolates a small part of your incoming sensory information and fixates on it. Awareness (peripheral awareness) is your mind's ability to devote some selection and focus to sensory information outside of your attention.

Example: If you're talking to a friend, your attention may be on their voice and the content of their speech. At the same time, you may be peripherally aware of a dog barking outside, the smell of bread baking in the other room, or your increasing need to pee.

One of the models-of-mind presented in TMI holds that exactly one thing can be in attention during a specific moment. If it feels like two things share your attention, it's a time-share (moments are very brief). Whichever object has the greatest share of moments will feel like it's at the center of your attention. Like all models, it's an imperfect map of reality, but it's a good one for us for now.

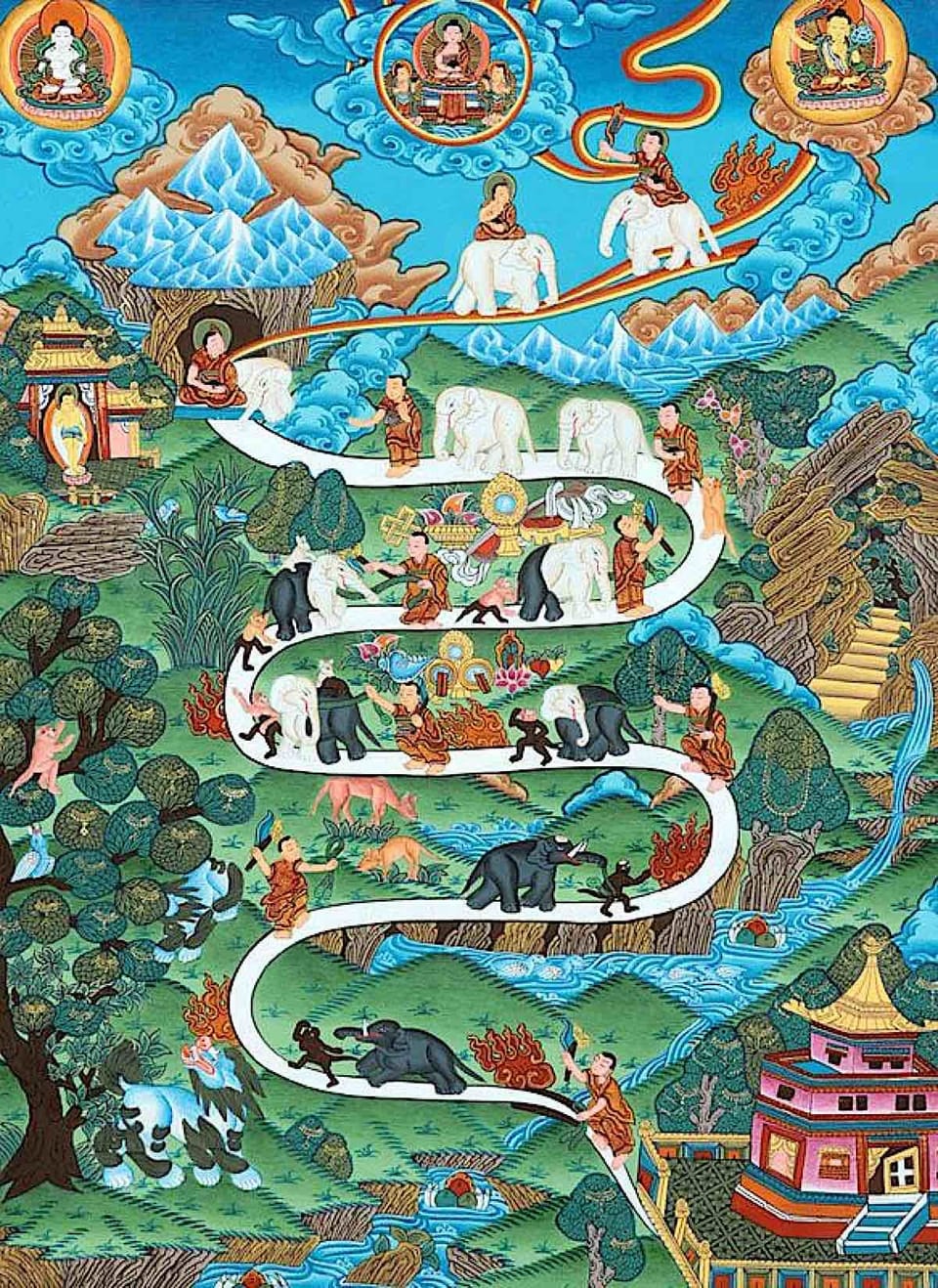

There are several "levels" or "stages" to concentration practice. The "elephant path" described in TMI is a useful framework. While we won't cover it in detail in this class, it's worth reading up on, and it informs our approach. It's also the header image for this page.

Some more vocabulary:

- Attention, awareness: see above

- Forgetting occurs when your meditation object has completely left your attention.

- Mind wandering is the involuntary movement of mind from one object to another. In concentration practice, it's what happens after forgetting.

- Distraction is anything that enters your attention other than your meditation object, without forgetting necessarily occurring. The meditation object is still in your attention, but it's not the only thing there.

- TMI has a distinction between "gross" and "subtle" distraction. Don't worry about it for now.

- If something is in your background awareness but not your attention, that doesn't count as a distraction. Attention-awareness is sort of a continuum; no need to be rigid about it.

Don't worry about subtle distractions for now. Work on forgetting less often. The line between forgetting and gross distraction isn't always obvious, but here's a good-enough razor: If someone were to ask you whether you were breathing in or out a moment ago, would you know the answer? If not, then forgetting occurred. If yes, then you may have been distracted, but you hadn't forgotten the breath.

With these terms clarified, we can elaborate on last week's instructions for breath meditation:

- Bring your attention to the object (e.g. breath sensations in the triangle)

- If you find that you have forgotten the breath or that a distraction has taken center stage in your attention, appreciate this moment of perception and gently bring your attention back to the breath.

- Optionally, take a moment to release any tension in your body and mind that you notice

- If you find yourself forgetting, the milestone of your progress is that the intervals between forgetting get longer and longer

- If you find yourself no longer forgetting (congratulations!), the milestone of your progress is to notice and release gross distractions sooner and sooner after they begin

Additions to concentration practice

If you find yourself getting distracted from the breath often, one reason may be that the mind doesn't find the breath interesting enough yet. You can temporarily increase the perceived interestingness with either of the following techniques.

- Labeling: Each time you notice a distraction, after appreciating and before returning to the breath, give a one-word label to the distraction. Some examples: "reminiscing", "sound", "back pain", "daydreaming", "bell craving". Don't spend more than a moment labeling. Choosing the "correct" label isn't important. Even broad categories like "thought", "physical feeling", or "sound" are fine. As you get more used to this, you can just use a single nonsense-word label like "bip" for everything.

- Connecting: Note how the characteristics of your breath change over time. For example, was your last in-breath longer or shorter than the previous in-breath? Was the air through your nostril cooler or warmer?

Eventually, you'll want to drop the extra technique and get back to a more basic breath concentration. But using these techniques is better than being constantly distracted. Treat it analogously to an assisted rep in lifting.

Troubleshooting concentration practice

Buddhism is full of lists. One of them is the list of five hindrances. For early forays into concentration practice, the most common obstacles that arise from the hindrances are:

- lack of motivation to practice

- mind wandering that leads to fixating on cravings or aversions

- "if only I had..."

- "I really can't wait to..."

- "this is SO boring..."

- "<person> is such an asshole..."

- impatience (craving the bell)

- low energy, drowsiness, dullness

- agitation

It's pretty common to start with lots of agitation and impatience. Then, as practice deepens, this may give way to dullness or even falling asleep. The logic of the latter is that as the mind quiets down, you have much less sensory input than you used to, and the mind finds this boring.

Below are a set of antidotes to dullness and agitation taken from TMI. They usually do the trick in the short term. Long term, the hindrances will fade as your practice deepens.

Antidotes to dullness:

- Light dullness (decreased sensory clarity)

- Engage more fully with the breath

- Open up awareness and let external sounds and sensation in

- Straighten up sitting position

- Open eyes a crack and let light in

- Take 3–5 deeper breaths

- Moderate dullness (sleepiness, repeated light dullness)

- Open eyes fully and meditate for a while with eyes open

- Release breath with resistance at lips (slight "raspberry")

- Squeeze and release perineum several times

- Clench hands until arms shaking then release.

- Clench whole body till shaking and release. Repeat.

- Severe dullness (hypnagogia, falling asleep)

- Stand up

- Practice walking meditation for a bit

- Splash water on your face

- Nap and come back

Regarding hindrances: it gets better. Lessening of the hindrances is one of the most predictable outcomes that comes with greater amounts of meditation (though it's not a consistent improvement; expect ups and downs).

Group sit: concentration on breath sensations

15min group sit, guided. Four-part transition to practice followed by concentration practice. Try using labeling or connecting.

Followed by around the room discussion of meditation experiences in the past week (including this class's group sit).

The three skills

One way of mapping meditative progress is to evaluate one's grasp of the three skills:

- Concentration: How stably the mind can keep a chosen object in its attention and other things out of attention

- Sense clarity: How much and in how much detail you perceive (through the "six sense-doors": the usual Western five plus mental formations)

- Equanimity: Evenness of mind and affect with respect to the mind's contents (non-grasping, non-aversion)

I believe this map is due to Shinzen Young (but I'm not sure). Any meditation will, over time, increase your grasp of all three skills. Some practices focus on one more than the other. Three of the four techniques we'll cover in this class each emphasize one of these: breath concentration for concentration, body scanning for sense clarity, and open awareness for equanimity. The fourth technique, loving-kindness (mettā), will grow your heart.

Closing around the room

What is one thing you will focus on in your practice this coming week?